By

Manzi, a mythology of the suburbs

would write about his absence an impossible elegy, a simple pure poem that includes a street barrell organ, a vidow and a trembling moon on which to lean on. And a hallway to steal kisses from a percale dress in the dark.

I like to believe that he was born in a big corral, celebrated with tough men’s whistlings and lullabies by washerwomen. He brought his childhood from the interior walking through a pampa that then was an infinite space to settle in the neighborhood of Boedo, on the corner that faces the embankment and breathes smelly gorges. And there he learned to hear with clarity the voice of those who do not own it. When he got in mis mind the idea of reading the classics like Evaristo Carriego he witnessed «the moon in a square of the backyard, an old man with a fighting cock, something, anything. Something that we cannot recover...» (Borges, Otras inquisiciones).

I like to believe that he was born in a big corral, celebrated with tough men’s whistlings and lullabies by washerwomen. He brought his childhood from the interior walking through a pampa that then was an infinite space to settle in the neighborhood of Boedo, on the corner that faces the embankment and breathes smelly gorges. And there he learned to hear with clarity the voice of those who do not own it. When he got in mis mind the idea of reading the classics like Evaristo Carriego he witnessed «the moon in a square of the backyard, an old man with a fighting cock, something, anything. Something that we cannot recover...» (Borges, Otras inquisiciones).

Maybe it was the rusty cage of a canary or the precise observation by González Castillo about some corner of Boedo that revealed the universe for him in an unusual fullness: the neighborhood.

In this orbit, among our letters, the names of Almafuerte (1884-1917) and Carriego (1883-1912) sparkle. The connoisseurs think that the latter, I don’t know if they are right, «discovered» the neighborhood as a subject matter for poetry. Probably, before him the outskirts had been the occasional and, even, accidental recipient of poems that touch them to refer to other things regarded as more decent. Undoubtedly, we can think that these were the poets that foresaw the miracle of what is simple and the simple anecdote.

In this panorama Homero Manzi appears, decided to leave behind the poetry of the obsessive academic meter, to tell us poems that he glimpses among a latticework. Like no one else he received the strength of what is there at sight and because of that it is unnoticed and he, with «eyes closed by sleep» and «a small bunch of rue behind his ear» (“Mano blanca”), built men that were not, exceptionally «literary», riders of spirited steeds but carters with skinny horses that trotted along alleys coming back to the big corral.

In this panorama Homero Manzi appears, decided to leave behind the poetry of the obsessive academic meter, to tell us poems that he glimpses among a latticework. Like no one else he received the strength of what is there at sight and because of that it is unnoticed and he, with «eyes closed by sleep» and «a small bunch of rue behind his ear» (“Mano blanca”), built men that were not, exceptionally «literary», riders of spirited steeds but carters with skinny horses that trotted along alleys coming back to the big corral.

Horacio Salas presented him as «the first one in turning the words included in tangos into poetry» so opening the arduous road that the genre had to follow to get a licence for the recognition in the «high spheres of culture», inscrutable circle that, historically, opens and closes on them.

In 1928 his tango “Viejo ciego” was known. It was regarded by many ones as the starting landmark of the new horizon that the poet opens for tango.

Con un lazarillo llegás por las noches

trayendo las quejas del viejo violín,

y en medio del humo

parece un fantoche

tu rara silueta de flaco rocín.

(With someone that guides your blindness you come every evening

bringing the complaints of your old violin,

and amidst the smoke your strange skinny horse-like silhouette

looks like a puppet)

There is neither allusion to tormented love, nor to the night landscape of anguish or bewilderment, nor to sordid brothels which meant darkness and were the birth of this genre we love.

Reader of the great poets, Manzi displayed a simple language, devoid, in general, of lunfardesque idioms, with which he managed to build images that reach us even to hurt us and make us long for a childhood of lost memories that some of us feel as if they were intimate despite we have not reached them. He felt the presence of the vacant lot with weeds and floods, from a far distant interior he already knew and which was hinted by the nearby country houses; of the grocery stores that vanish with the passing of time... without witnesses. Of what would disappear forever. And he knew how to open a subject matter different to the ones existing then, upon the nostalgia of the daily things.

Reader of the great poets, Manzi displayed a simple language, devoid, in general, of lunfardesque idioms, with which he managed to build images that reach us even to hurt us and make us long for a childhood of lost memories that some of us feel as if they were intimate despite we have not reached them. He felt the presence of the vacant lot with weeds and floods, from a far distant interior he already knew and which was hinted by the nearby country houses; of the grocery stores that vanish with the passing of time... without witnesses. Of what would disappear forever. And he knew how to open a subject matter different to the ones existing then, upon the nostalgia of the daily things.

This style was preceded by the ancient trend with picaresque lyrics born in the southern brothels; the trend of unrequited love that necessarily led to a lament because of loneliness and abandonment; and the issue of resignation and protest that maybe Enrique Santos Discépolo opened with “Qué vachaché” two years before “Viejo ciego”.

The Lorca’s influence in his oeuvre, that some have unfairly overestimated, is evidenced in some common elements and in the treatment of some rhymes with clear airs of romance.

In Sebastián Piana he found the hidden music that his dancing lines originally pull along. With him he wrote “Milonga sentimental”, “Milonga del novecientos”, both recorded by Carlos Gardel, and “Milonga triste”, among others.

Time, with true justice, has popularized some of his best pieces: “Malena”, a meeting of unsurpassable comparisons:

Tus ojos son oscuros como el olvido,

tus labios apretados como el rencor,

tus manos dos palomas que sienten frío,

tus venas tienen sangre de bandoneón.

(Your eyes are so dark like oblivion,

your lips are tightly closed like grudge,

your hands are just two shivering doves,

and in your veins bandoneon blood flows)

“El último organito”, an elegy and a fable from the outskits:

Las ruedas embarradas del último organito

vendrán desde la tarde buscando el arrabal,

con un caballo flaco, un rengo y un monito

y un coro de muchachas vertidas de percal.

(The muddy wheels of the last street barrel organ

will come from the evening in search of the outskirts,

with a skinny horse, a cripple and a little monkey

and a choir of girls dressed in percale)

With “Eufemio Pizarro” he pays a respectful homage to those men that represent time, reality and legend.

Decir Eufemio Pizarro

es dibujar, sin querer,

con el tizón de un cigarro

la extraña gloria con barro y ayer

de aquel señor de almacén.

(Saying Eufemio Pizarro is to, involuntarily, draw

with the coal of a cigar the strange glory with mud and yesterday

of that man of the grocery store)

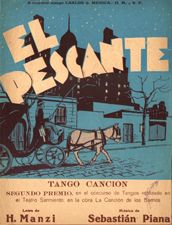

“Fuimos”, “De barro”, “Ninguna”, “El pescante” and “Barrio de tango” in which he tells us about «the moon washing against the mud» and he warns about the «goodbye-mystery that a train sows».

He memorably dived into the movies and politics, an environment in which he defined himself as a revolutionary in the Yrigoyen’s tradition and behaved according to that. He was expelled from the Radical party when his convictions urged him, like many others, to be a Peronist in 1945 and later to quit that party also.

Suffocated by the anguish of a near death he confessed he knew what was unrecoverable and he became eternal in the noblest heaven a man can aspire to: the tradition of a people that whistles and sings his oeuvre... forever.

Sur,

paredón y después.

Sur,

una luz de almacén (...)

Las calles y las lunas suburbanas

y mi amor y tu ventana

todo ha muerto ya lo sé...

(South, big wall and later. South, a grocery store’s light (...)

The suburban streets and the moon and my love and your window

everything is dead I know quite well...)