By

The famous dancers. Glory and decline of El Cachafaz and El Vasco Aín

t is a general opinion that El Cachafaz was the best tango dancer, even though others also achieved fame with so difficult artistry. He was nearly sixty in 1942 and he went on shining, as if wrinkles or white hair were unable to beat the boy who entered his glory in a dark yard, dancing at a contest of tango orillero (from the outskirts) and tango de salón (for dancing salons) for an exclusively male public. But he already was, at that time, a master who had learnt to very well assimilate the lessons of the early orilleros who created the tango dance. His nickname was owed to his mother, tired of his escapes and his street adventures.

He was called El Cachafaz to refer to the wanderings of his behavior, when on the Abasto corners (the neighborhood of Buenos Aires which knew of Gardel’s rise to singing) he flaunted by dancing to the beat of the barrel organs, or he went into the academias (dancing rooms) to test himself as a man or a dancer. But Benito Bianquet (this was his real name) was not born at el Abasto, but in south Barracas, an opposite neighborhood. However, he was always around el Abasto, and near this area he achieved his early honors. (Todo Tango Director's Note: El Cachafaz’s true name was Ovidio José Bianquet)

He was called El Cachafaz to refer to the wanderings of his behavior, when on the Abasto corners (the neighborhood of Buenos Aires which knew of Gardel’s rise to singing) he flaunted by dancing to the beat of the barrel organs, or he went into the academias (dancing rooms) to test himself as a man or a dancer. But Benito Bianquet (this was his real name) was not born at el Abasto, but in south Barracas, an opposite neighborhood. However, he was always around el Abasto, and near this area he achieved his early honors. (Todo Tango Director's Note: El Cachafaz’s true name was Ovidio José Bianquet)

Two dedicated tangos

He was certainly, then, the dancer from the outskirts. The dancer for the dense customers of the houses with bad reputation. But as his success was growing, as he was jumping from big yards to the most elegant places, he commenced to polish his technique and even to embellish his steps, amazing Hansen’s or El Velódromo’s customers.

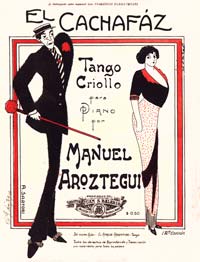

A tango from 1913, by Manuel Aróztegui, titled “El Cachafaz” (Todo Tango Director's Note: As for the tango “El Cachafaz” dedicated to the actor Florencio Parraviccini, this fact does not imply to deny the reason of its inspiration. Although for many people it has nothing to do with the dancer) helped to immortalize the name of the best tango dancer.

Another tango, named “Bailarín compadrito” and sung by Gardel, was, on the other hand, inspired in his life. For example, it points out that his beginnings were in south Barracas. Even though the lyric is a double-edged tribute, because, in sum, it just throws in his face the fact of his passing from the outskirts world to the more elegant world of salons and high society circles. In fact, Bianquet started to polish more and more his style of dancing, erasing roughness and coarseness in step movement, showing an admirable choreographic capacity, and simultaneously he achieved wide prestige in the most renowned dancing centers (such as Los cabreros or El gran bonete). The result was that he finally had to teach the aristocratic ladies to dance tango at a downtown theater. He charged quite expensive fees for his lessons and all the elegant world in Buenos Aires (who, due to the boom of this music in Europe, had forgotten about his dark origins) was after him to be taught. This teaching is portrayed with a light sarcasm in the lyric aforementioned:

Cualquiera iba a decirte,

che reo de otros días,

que un día llegarías

a rey del cabaret

y pa enseñar tus cortes

pondrías academia...

Jump towards Europe

But the admission to the salons was what Bianquet needed to expand his fame to Europe. By 1920 he arrived in Paris and quickly succeeded. His creole elegance, his figure, his artistry more and more polished and at the same time more beautiful, opened for him the doors of every Parisian salon. This period coincides either with his fame or with his better financial fortune. Benito Bianquet got money in enormous amounts. But in the end, in spite of the salons and the full dress, he kept on being the same rascal who disquieted his mother when a teenager, so he sticked faithful to a disordered and hazardous existence. On his return from Europe only the memory of the money earned was left, as had happened before with the fortune he got in Buenos Aires. He had no other choice but to go on working, to go on living from day to day and depending on lucky strikes, which some day drove him to a theater stage and another day threw him into a low class cabaret.

Anyhow, those who saw him walking along Corrientes street in his late years, always erect, always ready to shine as at his best times, had no doubt that for Bianquet his life began and ended with dancing, with a tango well danced. His partner (Carmen Calderón) had helped to his glory and the dancing team they represented was really wonderful. In 1942 they were in Mar del Plata performing in a boîte, surrounded by the few friends who knew their old glories, when his death took place. It was a few minutes after finishing their show and at the time he was going for a drink to relieve himself of his fatigue. Outdoors, the young were singing boleros and were beginning to regard tango with indifference. Indoors, at the boîte, a man closed his eyes for good, maybe thinking that the lyrics dedicated to him one day, were not completely mistaken when they pointed out his hopeless old age. "ahora triste y viejo te ves en el espejo del loco cabaret" (now sad and old you look yourself on the mirror of the crazy cabaret). His friends had to collect eight hundred pesos to pay the funeral. Bianquet had no single coin on him.

Anyhow, those who saw him walking along Corrientes street in his late years, always erect, always ready to shine as at his best times, had no doubt that for Bianquet his life began and ended with dancing, with a tango well danced. His partner (Carmen Calderón) had helped to his glory and the dancing team they represented was really wonderful. In 1942 they were in Mar del Plata performing in a boîte, surrounded by the few friends who knew their old glories, when his death took place. It was a few minutes after finishing their show and at the time he was going for a drink to relieve himself of his fatigue. Outdoors, the young were singing boleros and were beginning to regard tango with indifference. Indoors, at the boîte, a man closed his eyes for good, maybe thinking that the lyrics dedicated to him one day, were not completely mistaken when they pointed out his hopeless old age. "ahora triste y viejo te ves en el espejo del loco cabaret" (now sad and old you look yourself on the mirror of the crazy cabaret). His friends had to collect eight hundred pesos to pay the funeral. Bianquet had no single coin on him.

El Vasco Aín story

Next to El Cachafaz, the name of Casimiro Aín also left a trail on the tango dancing history. When he left from Buenos Aires towards Europe, he was known as El Vasco, a nickname that reminded his ancestry.

But his fame had not Argentina as a stage but, especially, countries like France, Spain, Italy, where his art found renewed triumphs. It was him who danced tango for the Pope Benedict XV, for example. In reality, his odyssey in the Old World (which preceded Bianquet’s for more than four years) was decisive for this music to succeed outside. Aín meant the arrival of the first serious tango dancer. The first in introducing a greater artistic wealth to dancing. Until 1926, approximately, the artist kept his kingdom untouched, even though El cachafaz’s arrival could have meant an important challenge. But the ten or fifteen years which modelled his career in Europe had been enough to make him an unquestionable attraction in cabarets and elegant salons. So his artistic biography is written far from the tango homeland, and Casimiro Aín’s name succeeded to say more in Paris or in Rome than in the Argentine capital.

In 1927 El Vasco returned to Buenos Aires and almost disappeared from public light. The details of this late stage of his life are unknown, except the fact that he underwent a surgical operation on his leg, what later derived in amputation. As a bitter irony, fate was reserving this ending with crutches, which (for a talented dancer, for a man who had bet all his life and his dreams on his experience as dancer) meant a true deadly blow. A few months after the operation, he died. The causes of his death are unknown, although is easy to imagine the drama he was obliged to endure when seeing himself maimed and with no possible future chance. Destiny so defeated a major dancer, he was cornered into solitude and oblivion.

Other figures

Two names do not make the history of a dance which, already in the early times, found a marvelous generation of profligates (as Carlos Vega said) capable of creating choreographic movements of unequaled beauty. But out of the long list of dancers who contributed to create, to spread tango, they are the most important. Nevertheless, the nickname of El mocho reminds us of a certain Undarz who achieved fame at the cabaret Royal (Corrientes, near Carlos Pellegrini street, where later the Tabarís was placed); the stage put forward figures as popular and famous as Juan Carlos Herrera or Tito Lusiardo; Pardo Santillán himself, whose fame at Hansen’s was total up to the day when he went out to dance with his partner to show his artistry to El Cachafaz (who had just arrived at the local), and the latter defeated the former with his acrobatics on the dance floor. The prowess nearly derived into police chronicle, but a friend of Bianquet’s called El Paisanito infused a volcanic calm with his knife. They were alone and in spite of this they managed in getting the control of it. That is to say, El Cachafaz managed to go on dancing. He had defeated Santillán for good and all the dancers who came before or after him (See a more detailed story of this event in an excerpt from the book by García Jiménez (Todo Tango Director’s Note: on this same section, under the heading Challenge for Dancers). His name is already a definitive symbol of danced tango.

Narration without mentioning author, published on the magazine Hechos Mundiales Nº1, Editorial Zig-Zag, Director: Edwin Harrington. Buenos Aires, 22 August 1967.