By

Discépolo and politics: «You’ll see that everything’s a lie…»

woman

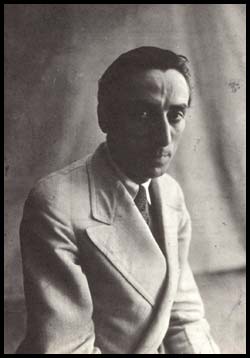

The skinny, crestfallen poet got off an automobile and headed, as he daily did, towards the wide door of Radio Belgrano. Through that door the lead figures used to enter, the others did it through a smaller door placed at one side. It was probably 1943, the radio aired its tango tunes that people used to sing round the corners.

Suddenly a young attractive woman tried to enter with him. When the doorman saw her, he stopped her: «-No, the girl can’t». The poet, who did not know the girl, turned back and told the doorman: «The lady comes with me and enters through this door». The poet was Enrique Santos Discépolo and the smiling, resolute blonde was a woman named Eva Duarte.

Suddenly a young attractive woman tried to enter with him. When the doorman saw her, he stopped her: «-No, the girl can’t». The poet, who did not know the girl, turned back and told the doorman: «The lady comes with me and enters through this door». The poet was Enrique Santos Discépolo and the smiling, resolute blonde was a woman named Eva Duarte.

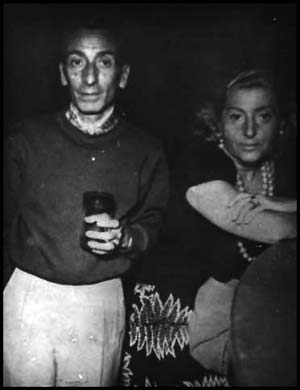

As she had an extraordinary memory —as Tania, renowned female singer and Enrique’s wife, used to say— she remembered what had happened on Radio Belgrano and one day, years later, asked her assistants to call Discépolo. She wanted to meet him. «That man is a gentleman.», said she. So the relationship between the poet and the future first lady began. They became close friends. Apparently, he had met Perón in Chile years before.

«The belly is queen and money is God»

Let’s go a couple of years back. September 6, 1930. The Armed Forces under the command of general Uriburu and backed by conservative sectors that rejected the policies of the government and the style carried out by Hipólito Yrigoyen effected the first military coup in the history of Argentine democracy. Two days before “Yira yira” had been recorded for the first time: «Verás que todo es mentira, verás que nada es amor...» (You’ll see that everything’s a lie, you’ll see that nothing means love)

In it, the author continued with a thematic line that had started in 1926 with “Qué vachaché”: a complaint before a ferocius, ruthless world. But now, that naïve character in “Qué vachaché” gives way to another one, more experienced, who had felt in his own flesh the misfortunes of life and recommends «never expect either some help or a hand or a favor».

In 1934 “Cambalache” appeared, in it he denounced out loud that «the world was and will be like shit». (A digression: In his memoirs Enrique Cadícamo, friend and partner in common adventures of his namesake, pointed out that his tango “Al mundo le falta un tornillo”, in which he deals with similar issues, is much earlier. «A simple coincidence» he said ironically in a prologue. It is fair to acknowledge dates but it is also forceful to accept that “Cambalache”… is “Cambalache”.)

«Something’s going to happen in Spain because the tango “Cambalache” was sung three times by Tania on request by the audience.», said Discépolo to the actor Osvaldo Miranda on an occasional encounter in the street. Soon thereafter the civil war broke out and the nazi regime was increasingly spreading until it ended up in a new war that involved the world.

In Enrique’s poetry there was no longing and melancholy for lost things devoured by the passing of time, so common in tango lyrics. There was an aching vision of life as struggle, as disillusionment; and of society, as a wild territory where lies and financial power are the ones which hold the conductor’s baton. (Perhaps Enrique’s only truly melancholic tango is “Cafetín de Buenos Aires”).

Discépolo covered tango lyrics, movies, theater and the radio. He always unclothed a heartbreaking political and social reality. He breathed the “rusted tin symphony” of the tenement houses where nauseas and dreams of thousands of people were piled up. He did not see there a poetical vignette that deserved a warm evocation but «a world where a garbage can was a trophy and a rat, a domestic animal… a mess of traveling cockroaches and people stacked not as persons but as things».

Movies and theater plays of that time provided a more picturesque vision of these dearths. Certainly, «the hunger of others is something that always amuse those who have had lunch», gracefully says Discepolín in a memorable scene of one of his movies. A Chaplin-like air, rightly insinuated Julián Centeya. A criollo Chaplin criollo and ours.

Peronism

Towards the late 40s Discépolo took part in the political and trade union competitions in SADAIC and he already showed his support for peronism. «According to Discépolo, who was not a politician, what peronism was doing was substantially a social change. And that was what he cared for.», states the historian and biographer of the poet, Norberto Galasso.

He began to collaborate with the electoral campaign for the presidential reelection of Perón. He did it through the official radio program “Pienso y digo lo que pienso” (I think and say what I think). In it Luis Sandrini and Tita Merello, among other figures of that time, had appeared. Later with Discépolo it changed its name to “¿A mí me la vas a contar?” (Are you going to tell me that?) and was addressed to a hypothetical interlocutor whom he named Mordisquito. The latter was a representation of the archetypal anti-peronist petty bourgeois.

In a warm tone, even affectionate, he told “Mordisquito” that previously children «used to taste cream from time to time» and now they «can go to school with a cow’s supply». “Mordisquito” complained about some problems of shortage, for example, cheese. Discepolín used to say: «There’s no cheese! What a problem! Are you going to tell me that that’s not a problem? Time before there was nothing at all, no money, no compensation for dismissal, no protection for the old... and you didn’t say anything... you saw a parade of desperate people and you stayed motionless.». And all the talks ended with a: «No, you’re not goin’ to tell me that!»

In a warm tone, even affectionate, he told “Mordisquito” that previously children «used to taste cream from time to time» and now they «can go to school with a cow’s supply». “Mordisquito” complained about some problems of shortage, for example, cheese. Discepolín used to say: «There’s no cheese! What a problem! Are you going to tell me that that’s not a problem? Time before there was nothing at all, no money, no compensation for dismissal, no protection for the old... and you didn’t say anything... you saw a parade of desperate people and you stayed motionless.». And all the talks ended with a: «No, you’re not goin’ to tell me that!»

Censorship: without Perón and with Perón

On other occasions we have already talked about the “purification of language” that imposed the military goverment of 1943, through Gustavo Martínez Zuviría (aka Hugo Wast), minister of Justice and Public Instruction together with Monsignor Franceschini. This venture mutilated an endless list of tango titles and lyrics. Several Discépolo’s pieces underwent this “purification”. For example, “Yira yira” after that was called “Dad vueltas, dad vueltas” (Turn around, turn around).

It is interesting to mention the fact that censorship to tango continued in the early years of the goverment of his friend, Perón, who lifted the ban in 1949. Sergio Pujol, biographer of Enrique, historian and professor in the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, told us that the Discépolo’s tango which had problems of airing under the Perón’s government was "Cafetín de Buenos Aires" because it supposedly conveyed a feeling of pessimism and discourage. «In my research –says Pujol- I did not find any decree or document that would certify the ban, but some journal notes appeared referring the discomfort Discepolín had about that issue.»

Finale

As it is known, peronism was triumphant in the elections of November 1951 but Discépolo’s luck changed again. His political opinions produced an expensive cost for him. Criticism began to harass him and it trespassed the limits of what was acceptable. There were threatenings, parcels that arrived with his records smashed into pieces or with excrements, alterations of his own lyrics in order to humiliate him. There were people, previously friendly, that changed a greeting for a spit on the floor when Discepolín appeared. When he presented a theater play he found out that somebody had bought all the tickets so that the actors would have an empty theater. When he entered a restaurant people whistled at him. This, for a man with a deep sensitiveness like Enrique’s, was lethal.

He quit writing, secluded himself in his house and stopped eating. «Soon I will have the injections shot on my overcoat.», launched the poet who was then just weighing 37 kilograms. He was examined by more than ten doctors. They never knew what he had.

Smothered by loneliness, by bitterness, one of the most outstanding figures that tango ever had, one of the wittiest voices that our country had had was dying due to deep sorrow.