By

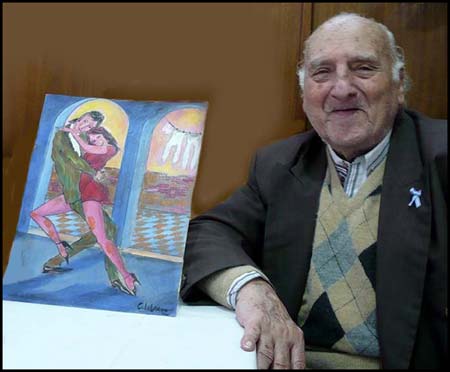

Germinal Lubrano, the tango painter

n September 15, 1918 the one who would be one of the most important painters of the tango oeuvre was born; he is today ninety-two; he paints an oil painting a day and he has finished over 600 pictures following the same pattern: the one inspired by tango lyrics.

Once his friend Edmundo Rivero told him: «The Argentine painters have not depicted tango...» Because of that Lubrano’s painting entered into the lyrics and the voices of Edmundo Rivero, Carlos Gardel, Enrique Santos Discépolo, Homero Manzi, Pascual Contursi...

By that time, Germinal Lubrano was already a consecrated painter. Far behind was his task as comics draftsman and his success as publisher with magazines like Carnaval, Descamisada and Risueña.

Son of Rosa Cortese, Argentine and porteña, and of Pascual Lubrano, born in Calabria, a manufacturer of taylor-made shoes. When he was a kid he was amazed by that long aisle where there were entire soles from floor to ceiling; one of the first things he did was to learn drawing shoes.

In 1920, because they were anarchists, his family had to settle in Montevideo, Uruguay. There he attended grade and secondary school; he later entered the Círculo de Bellas Artes. Germinal went on working with his father but it was stronger his liking for drawing than shoe manufacturing; he made the shoe patterns to scale and he devised the models as the best designer.

Longing for home, after several years, they returned to Buenos Aires, precisely to the neighborhood of Floresta.

Again in the house where he lived as a child, Germinal began to work with a Spanish draftsman, José Sánchez, who was in charge of the advertising of the Maple furniture store and Zapatos Tonsa (shoes). He made the drawings of the shoes in black ink. Was there anyone more suitable than that boy that polished somebody else’s shoes and helped his father to design his own shoes? Furthermore at the same local lottery tickets were sold and there was a courier service.

However, very soon, with his restless age –seventeen years-old-, he entered the editorial department of the Viva Cien Años magazine, where he learnt about page layout, one thing more to delve into journalism. Furthermore, Viva Cien Años will be as a bridge for him to introduce himself into the editorial office of the newly opened Patoruzú magazine where he was seen by no less than Luis Alberto Reilly. Then Lubrano’s drawings had an outstanding place in the brand-new magazine alongside those of Dante Quinterno himself, Poch, Divito, Ferro, Guratti, Muñiz, José L. Salinas... But he had to go to military service, by that time an obligation (he was 20 then): «It cut me in two, a year lost in the Infantry Regiment General Belgrano Nº 3» —he regrets— «When I came back to civil life the magazine had its staff full and was on a budget cut plan...»

But what Germinal recalls very sadly of this period is his mother’s death. His sister Lucrecia, meanwhile, had married and his father had reorganized his own life.

Lubrano moved to a room in a building located on Maipú Street, «just upstairs the Marabú», he added cunningly. By that time the morning paper Libre Palabra (Free Word) appeared and he introduced a new character, still without name. But Franchi, director of the paper, named him Don Yacumín: «He was a little old man with a mischievous behavior towards girls...»

Also by that time the Estrellas magazine was released. He was in charge of the drawings and also of its layout.

Besides Don Yacumín in Libre Palabra he published in El Pampero a comic strip entitled Bien Porteño. Later he would add his character called Vivonet in Risueña.

He was also summoned for the layout of the ¡Boca...! magazine; he still remembers that they used to begin their work after the soccer match and went on until 4 a.m. It was a ten-year tenure in which he worked alongside Julián Centeya.

He indeed admits that despite those long working hours he liked to live in clover:

«Being a typical boy of the 40s I liked to dress well; generally I wore an English cashmere suit, a shirt with a starched collar which by that time was sold apart and was sent to be ironed. I wore a white silk neckerchief; nubuck suede, kidskin, or patent leather stringed shoes... “A la cachetada” hairstyle, hair plastered straight back from the temples to the neck. I copied that hairstyle from the guys who went to dancehalls in the 40s...»

He used to live well even though he worked hard. But despite it did not bother him very much he had a sort of remorse when he wondered: «There is a club which does not publish a magazine and it’s the one I love!» So the Independiente magazine was born. He released it with a subtitle: Los diablos rojos de Avellaneda (The Red Devils of Avellaneda) and it sold around 40.000 copies; In this venture he was also accompanied by Julián Centeya.

«In 1945 I was having coffee at a barroom and, through the window glass I saw a demonstration group passing by. A boy who carried a shirt tied to a stick attracted my attention. From the table at the bar I sketched a drawing and when I finished it I realized it was like a logo.»

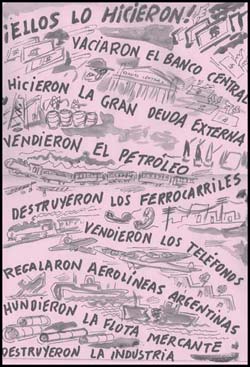

But it would be more than a logo because, based on that idea, Descamisada was born, a humor magazine in favor of the newly appeared Peronism. Its first number was published on January 22, 1946.

But it would be more than a logo because, based on that idea, Descamisada was born, a humor magazine in favor of the newly appeared Peronism. Its first number was published on January 22, 1946.

Today, Germinal Lubrano displays that same humor with commitment —but fully updated— in the blog Descamisada 2010. But let’s go back to the 40s: although he went on with the magazine, Lubrano was beginning to feel the need of devoting himself completely to painting. And that aspect does not admit concessions: «A painting has to stand for something, otherwise, if it says nothing it’s nothing!»

With a fully figurative style, humble characters and the people of the earth and the neighborhood are depicted in his paintings. In the 90s the centennial of the Avenida de Mayo was part of his inspiration.

«The idea was amazing... to present an exhibition on a subject like a traditional avenue of our beloved Buenos Aires seemed to us nearly impossible. However, the Avenida de Mayo attracted us with strength and inspiration.»

His words are backed by the 21 works exhibited in the Art Gallery of the Centro de comunicaciones CID, among them: Pyramid of May, Edificio Barolo, Pedemonte, Café Tortoni, Los 36 billares, the Cathedral, Castelar Hotel, the Well of the Cabildo, Restaurant Don Pipón...

And on that traditional avenue of Buenos Aires is also the Academia Nacional del Tango where Lubrano exhibited oil paintings with which he began to graphically portray tango on December 11, 1996 (Tango Day). Some months later he continued his exhibition on April 30, 1997 at the Academia Porteña del Lunfardo; in this case, the catalogue was augmented with Edmundo Rivero’s face drawn by the painter and the lyrics that the former dedicated to the latter:

Labura de pintor y en extendida

superficie total, el arte expresa

con plástica materia, la certeza

de fijar la pasión que está escondida...

He works as a painter and on an extended

total surface his art expresses

with plastic material the certainty

of grasping the passion that is hidden...

Director's note: Germinal Lubrano died a couple of years after this article was written on January 18, 2012.