By

The “orquestas típicas” and their recordings, 1910-1912

he so-called orquestas típicas, even though they are primarily associated with the spread of tango, had in the 10s and the 20s a role not many times recognized: they were the vehicle for spreading all the danceable music in our country.

This non-exclusivity as for tango took place in its recording beginnings, increased as from 1912 and peaked in 1913 when in the recordings the orquestas típicas completely displaced the other kinds of aggregations like the saloon orchestras, bands and rondallas.

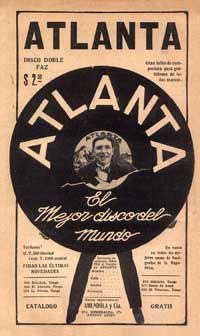

Unfortunately, except for the case of Victor, the exact dates of the recording sessions are not known. Consequently, estimates had to be made by means of collateral data. The most obvious ones were the ads about release of records but they did not always indicate the repertoires and, in any case, they were a few numbers by way of example. The usual thing was to find the intriguing announcements of this kind: «The new XXX records with the latest news have arrived!» without explaining which they were. Or also the repeated use of the illustration of a certain record label by which you very well know its date of release but ignore all about other contemporary recordings.

Unfortunately, except for the case of Victor, the exact dates of the recording sessions are not known. Consequently, estimates had to be made by means of collateral data. The most obvious ones were the ads about release of records but they did not always indicate the repertoires and, in any case, they were a few numbers by way of example. The usual thing was to find the intriguing announcements of this kind: «The new XXX records with the latest news have arrived!» without explaining which they were. Or also the repeated use of the illustration of a certain record label by which you very well know its date of release but ignore all about other contemporary recordings.

Anyway, on these grounds and also consulting those catalogues to which we can have access, if the listings have been sorted by the so-called «matrix numbers» (the chronological identification of the successive recordings), we can begin to date them with a reasonable certainty. For that you have to take into account that until 1919, even though recordings were cut in our country, the records were not manufactured here but abroad: in Germany, the United States or Brazil. We have to estimate the time it took to send them, how long the manufacturing process was, the time to bring them back, the customs proceedings, their dispatch and finally their release for sale. These time spans were generally nearly six months. Then, for example, if a record was announced in August we can estimate that it was recorded around February or March.

We can get another clue from a technical aspect: the wax matrix to be recorded had to be at around a temperature of 40º to be suitable for recording. For that, the «biscuits» were heated while they were rotating under the light of incandescent lamps. But to make this vital aspect easier the recording sessions, whenever was possible, took place during the warm months. Even though we cannot say that they exclusively were held at those seasons, that is another clue to help us date them.

This concept would not be valid in the case of new labels or a new manager of an established label that was starting its activities because the strategy was launching its products into the market at the beginning of the commercial year, let us say, in March or April. In these cases, and taking into account the time of the processes above mentioned, the recordings were made in winter or spring of the previous year.

We know that the name Orquesta Típica Criolla was coined by Vicente Greco on occasion of his recordings made for the Columbia company in the early 1910 or maybe the late 1909. The reason for this name was precisely meant for that the buyer of discs would know that it was an orchestra with bandoneon and whose members were from the tango milieu. This inicial series consisted of 17 tangos, 2 waltzes and 2 polkas in correlative matrices which meant no more than a two-day work.

Even though the success of these records was enormous, in the following years the record industry did not try to repeat this kind of recordings, whether by Greco himself or by another orquesta típica. I was unable to find a satisfying explanation for this gap because the market was eager (as will be verified after 1912) and there were enterprises of different labels that owned recording studios. And, of course, there were aggregations that could have been summoned.

Whatever the reasons, only in the early 1912 these kinds of recordings were resumed, and were massively made by Victor, Columbia and Atlanta as to catch up with the time wasted. It is worthwhile to say that for this time orquesta típica, in general, meant a quartet of bandoneon, violin, flute and guitar (or piano). And even, in some cases, a trio put together with these instruments.

It was as well customary that a renowned leader was required by several labels for a year. Such was the case of the bandoneon player Genaro Espósito (Tano Genaro or Gennaro) in his recordings for Victor in 1912 —as from January 19— fronting a quartet of bandoneon, violin, guitar and clarinet instead of the customary flute. A total of 11 tangos and 2 waltzes were released for sale.

For Columbia he recorded under the name Orquesta Típica Gennaro that was a trio lined up by its leader on bandoneon, Roberto Firpo on piano and Tito Roccatagliata on violin. They cut a total of 10 numbers, all were tangos.

Furthermore, he began to record for Atlanta as Quinteto Criollo Tano Genaro. Despite this label generally named its aggregations as quintets it turned out that it was a commercial gimmick because in all cases they were quartets and even trios. The latter would be the Tano Genaro’s case which, according to our ears, it seems to include bandoneon, piano and violin. By reading the composers’ names of the series of 12 tangos, 5 waltzes and 1 zamacueca it seems to be the same lineup as in Columbia. This assertion is backed by the fact that the Rondalla Criolla Firpo had simultaneously recorded a total of 5 tangos. It is heard like a trio of piano, violin and bandoneon which foretells his split with Firpo in order to put together his own orchestra which, strikingly, included Tito Roccatagliata as violinist. Finally, let us say that Tano Genaro recorded four bandoneon solos which were all waltzes.

Also in this prolific 1912 an orchestra, that later would be an archetype of the style then in vogue, recorded: the quartet headed by Juan Maglio (Pacho) on bandoneon with Pepino Bonnano on Stroh violin, Carlos Hernani Macchi on flute and Luciano Ríos on guitar. For Columbia they recorded 73 tangos, 11 waltzes, 4 polkas and 2 folk airs. Maglio also cut 2 bandoneon solos: a tango and a mazurka.

Also in this prolific 1912 an orchestra, that later would be an archetype of the style then in vogue, recorded: the quartet headed by Juan Maglio (Pacho) on bandoneon with Pepino Bonnano on Stroh violin, Carlos Hernani Macchi on flute and Luciano Ríos on guitar. For Columbia they recorded 73 tangos, 11 waltzes, 4 polkas and 2 folk airs. Maglio also cut 2 bandoneon solos: a tango and a mazurka.

Vicente Greco was summoned for a second series for Columbia and contributed the novelty of having replaced the 1910 guitar for a piano. As for the reasons above it is not possible to exactly precise the dates, it remains doubtful if this was the first aggregation that recorded with piano or the one led by Tano Genaro was. There are not doubts as for Columbia because the matrices by Greco are previous to the ones by Tano. But did the latter record firstly for Columbia or for Atlanta? By now we don’t know it.

Likewise, Greco was in the winter or spring of 1912 an artist for Atlanta and his orchestra was known as Quinteto Criollo Garrote. Remembering the implicance of the name quinteto, it is necessary to explain that Garrote was the nickname of its leader. His quartet started the series with piano, but the last matrices were with guitar accompaniment indicating that the choice for piano was not yet fully decided. They were a total of 18 tangos, 1 waltz and 1 mazurka.

Another figure of the Atlanta label was Augusto Berto who fronted another Quinteto Criollo which was, in fact, a quartet of bandoneon, violin, flute and guitar. It recorded 5 tangos, 2 waltzes, 1 polka and 1 march-polka. Despite the restricted initial repertoire this aggregation would be the one which would record most in the period 1913-14 for this label.

Also and always in 1912 we find in Atlanta the Rondalla Bevilacqua, that despite not being known as orquesta típica, was a trio of piano, violin and bandoneon that recorded 6 tangos.

Here we stop with this research and in the following part we shall see the recording activity of the orquestas típicas in the period 1913/14.